you can't scale clarity

i've been thinking a lot about what it means to build software now that AI can write code better than most people. there's a few memes going around to the tune of "i can't wait for 50x agency" or "imagine thousands of agents working on your behalf". and yet my intuition just can't seem to agree with these stories floating around on twitter.

people are clearly missing something. i think about a product like Dropbox — a company with thousands of engineers — and ask myself, 'when was the last time that product actually changed'? clearly output does not scale linearly with additional manpower. not even close. there are obvious diminishing returns, but how much?

actually we already have a way to quantify the exact limits of this theoretical speedup.

amdahl's law

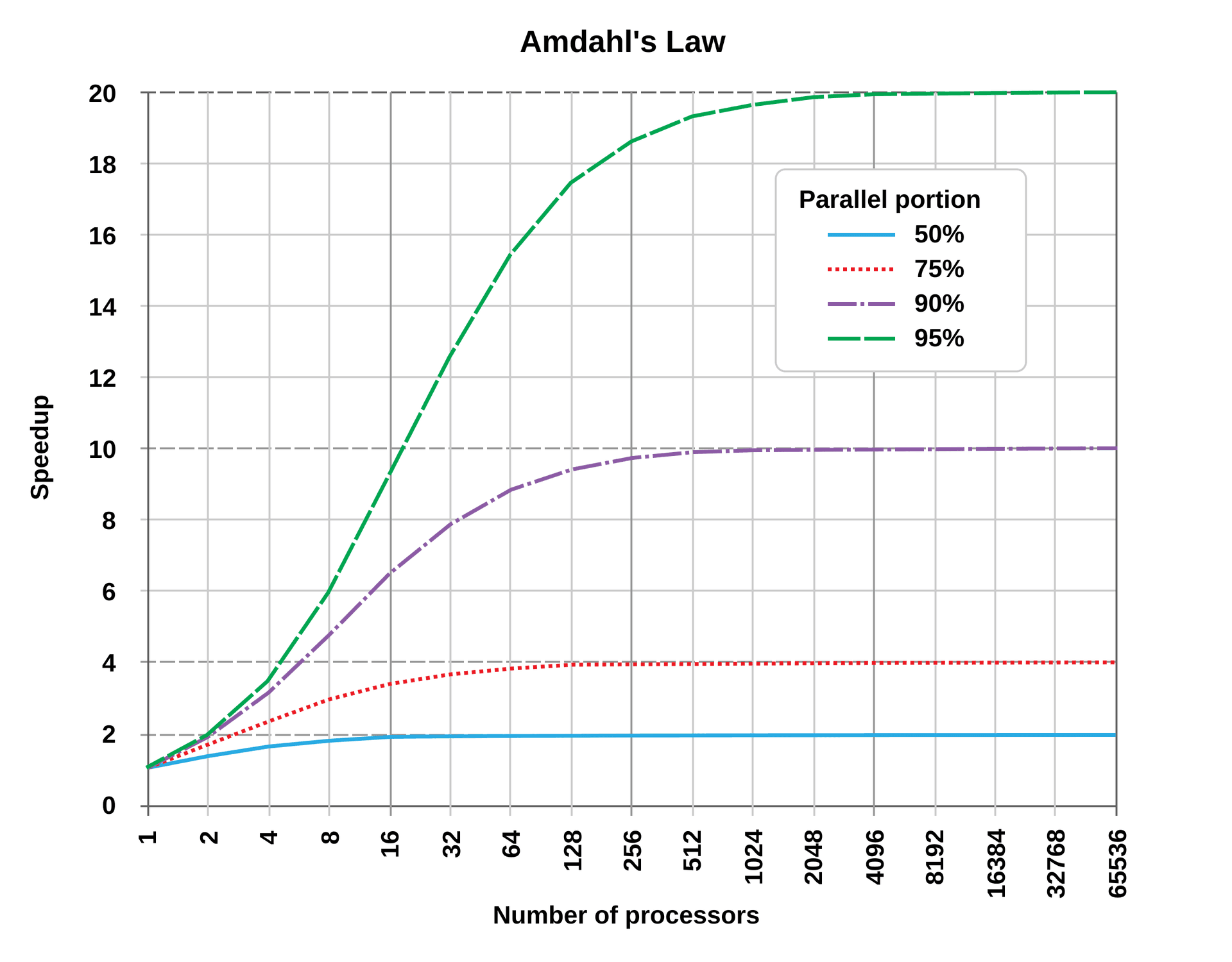

the formula was proposed by Gene Amdahl in 1967 [1], and it gives us a way to quantify the maximum speedup of a task when more resources are added. specifically, it describes the relationship between the portion of a task we can optimize, and that which we cannot. often used in parallel computing, we can apply it to this problem in the same way:

the overall speedup of a given task will be limited by whatever portion of the work has to be done sequentially. so that even if we have thousands of agents — or millions even — we remain the bottleneck. and a hard bottleneck at that. even if you parallelize 99% of a process to infinity, that remaining 1% sets a hard ceiling on the speed of light.

the asymptotes here are a sobering antidote to the kool-aid.. and there's nothing like a little splash of cold, raw formulas to sober up from the twitter memechamber.

design is the new bottleneck

so if AI gives us unlimited engineering "manpower", what's left? in other words, what are the serial bottlenecks that can't be parallelized away?

the answer, i believe, is that we don't know what to build. we are idea-limited, not resource-limited; and the speed at which we can come to grips with a problem sets the serial limit on how fast we can execute in a world where execution is cheap.

this is what i am calling design in this context.

design is not just about pretty colors and decoration. it is the foundational work of framing the problem correctly. of asking the first questions: what problem are we even trying to solve? what does the user actually need? what do they actually want? we all know the advice: "build something people want" - and yet it remains an elusive problem which few manage to solve.

a great designer is part detective, part psychologist, part philosopher. they chase down the hidden assumptions that shape our understanding of the problem itself.

AI is useless until you can articulate what you actually want — in other words, until you can ask the right question. but asking the right question presupposes a latent understanding of the problem, which is precisely the dark and ambiguous space in which the designer operates.

design is that frontier: the work of fumbling in the dark, of coining new language to describe new possibilities, of inventing the frame that makes the problem legible in the first place. that is not work you can outsource to a machine (at least not today). AI will happily optimize the wrong thing with incredible efficiency—but it won't tell you that you're asking the wrong question.

yet if asking the right question presupposes a latent understanding of the problem—because a question is merely its answer with noise—then i think we have identified our sneaky little bottleneck: we are limited by human understanding. we are limited by our own lack of clarity.

clarity doesn't parallelize

so how can we think about the scaling laws behind understanding?

the first thing to know is that coordination costs scale quadratically. the number of communication channels in a group of people is given by n(n-1)/2. at 5 people, that's 10 channels. at 15 it's 105. at 50 it's 1,225. the time spent syncing grows so fast that it eventually exceeds the time spent thinking and actually doing the work. understanding is especially vulnerable to this cost because it not only requires sync, but high-bandwidth sync.

legibility kills nuance. the larger the group, the more things have to be made explicit. but articulating any idea simplifies it. you end up with a compressed, warped version of it, not the idea itself. small teams can operate on vibes, shared intuition, and give voice to fetal thoughts - because of the shared context which forms the basis of their communication. understanding requires holding the whole problem in your head at once, and being able to conceptualize a coherent vision of the relationship between all its parts. it means trying to balance a thousand details at the same time, and trying to fit them into their place in the puzzle. more people = division of labor = each person only holds a small piece. when attention fragments like this, you miss the insight which tends to come from unexpected connections across the different pieces.

small teams also have the advantage of high-trust. new ideas are fragile, and they often sound wrong before they are proved right. groups apply social pressure towards consensus, towards a regression to the mean. the lowest common denominator forms the basis of consensus, and it is very hard to raise that bar as the number of people grows. taste + judgment are anti-democratic by nature.

apple had it right

Apple understood this, and through Jobs' initiative encoded a cultural DNA that placed design at the top of the hierarchy (literally). after being urged by Esslinger, who was the founder of Frog Design and secured a contract to help redesign the Macintosh, Jobs reorganized the company completely and inverted the previous engineering-supremacy culture that had existed before:

Designers at Apple reported to the company's engineers and saw no reason to change their weak position within the organizational hierarchy—but I did because design must be "top down". From the start of my career, I insisted on working directly with the owners or leaders of companies that contracted with me, because design cannot succeed from the "bottom up." It was clear to me that it would be impossible to achieve Steve's goal if designers remained servants at the mercy of conservative engineers. Steve agreed. -- Esslinger [2]

Jony Ive has talked about the fact that it was always clear that they would keep the design team at Apple very small (< 15), and worked very hard to preserve this decision. they would meet at each other's houses, and gather in small groups to discuss the design problems at hand in this high-trust environment.

and Apple became the most valuable company on earth operating on these cultural principles.

designing a delta force

i'm not sure that people have actually adjusted to a world where these are the constraints. almost certainly not, if history is any guide. humans tend to be very slow to adapt to new technologies, and only then with great reluctance and pain. if you are - like me - a believer in technology, and see its progress as inevitable, then the only sensible thing to do is to come to grips with it as soon as possible.

we, as designers of our own productivity, can start to think about how to shape our teams + companies around the profound structural changes which are taking place. while others focus on how they can run 20 instances of Claude Code in tmux windows, or how they can have Codex working on 100 issues at once, we remain sober because we know the asymptotes. we know this is only an illusion of increased output, and that we are not missing out because we don't subscribe to the hype.

these are a few principles that i've outlined for starting to approach this problem:

- stay small on purpose.

- hire for taste + agency.

- n+1 means more than ever.

- general > specialized.

stay small.

keeping our teams small and optimizing for high-signal environments follows naturally from the fact that clarity doesn't parallelize, and coordination costs scale faster than the advantages of headcount when individuals are augmented.

iteration speed is everything. the consensus loop must be tight and high-trust; velocity comes from removing people not adding them.

hire for taste + agency.

with intelligence on tap, execution is cheap. the new paradigm is one where taste and agency dominate. agency means people who will take initiative, who will seek out solutions to new problems on their own, who aren't afraid to use new tools if it means they can do more than they could without them.

taste is subjective of course. in a world where humans are primarily steering the output of AI, we become the curators who have to make the opinionated, subjective judgment of value between A + B. and it must also be protected from democracy. clarity dilutes as the crowd grows. the lowest common denominator becomes the inevitable output.

n+1 means more than ever.

power laws occur everywhere in the world. and yet they are hard to understand because our brains don't seem to be wired very well for extreme distributions. variation in output between individuals is more dramatic than most would like to admit.

some variation of Price's Law seems to dominate creative output in most domains. that law states that the square root of the number of contributors produce half of the output (originally formulated regarding scientific publications) - so that if you have 10,000 contributors, the top 1% contribute 50% of the total output. it isn't exactly clear how you would quantify the total number of contributors here, but some studies suggest output variation of 20-25x [3] among programmers. and i personally suspect the difference may be even greater than this.

if Joe produces 5 apples, and Sally produces 100 apples, then even a simple constant multiple of augmentation produces vastly greater absolute differences:

| Multiplier | Joe | Sally |

|---|---|---|

| 1x (baseline) | 5 | 100 |

| 5x | 25 | 500 |

| 10x | 50 | 1,000 |

| 20x | 100 | 2,000 |

| 100x | 500 | 10,000 |

while the ratio stays constant (20:1), the absolute gap explodes.

and the consequences of augmentation may even be more dramatic than a constant ratio in fact—because exceptional people were more bottlenecked by execution than median people. outliers will reap disproportionate advantages, the median only marginal gains.

thus every addition to the team must be intentional, as the opportunity cost of a bad decision is higher than ever.

general > specialized.

specialization made sense when execution was the bottleneck. now you need people who can see across boundaries. you can summon the expertise of 80% of the specialists knowledge on demand because of AI. so there is an inevitable commoditization of these skills, and a premium which will be set on the generalists ability to operate across domains.

when understanding is the bottleneck, generalists become valuable as the ones that can traverse cross-domain space with greater fluidity + speed than specialists can. they're valuable because they can hold enough of the problem in their head to see the connections that specialists miss, and communication overhead is far lower.

closing thoughts

in a world where execution is cheap, the only real advantage is knowing what's worth executing. when anyone can build, taste + clarity become the only moats. the winners won't be those who figure out how to run more agents in parallel. they'll be the small, opinionated teams who know what's worth building in the first place, and who move fast enough because there's no one to wait for.

[1] Amdahl's law. Wikipedia.

[2] Esslinger, Hartmut (2013). Keep It Simple: The Early Design Years of Apple. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers.

[3] Sackman, H.; Erikson, W.J.; Grant, E.E. (January 1968). "Exploratory Experimental Studies Comparing Online and Offline Programming Performance". Communications of the ACM. 11 (1): 3–11.